Overview

Rust is a programming language with the goal of "empowering everyone to build reliable and efficient software."

Features of Rust include:

- performance on par with C/C++

- memory-efficiency

- ownership model that guarantees memory-safety and thread-safety

- rich, static type system with type inference

- targets LLVM to enable Rust programs to run on a wide variety of platforms

- ability to call and be called by languages that support the C Application Binary Interface (ABI) with no overhead (includes C, C++, Go, Java, Python, and Ruby)

- functional - Functions can be stored in variables, passed to functions, and returned from functions.

- somewhat object-oriented - Structs can have fields and methods (like classes). These can be public or private, providing encapsulation. Structs can implement traits which are like interfaces. Traits can be used as types which achieves polymorphism. Structs can have fields whose types are other struct types which achieves composition, but they cannot inherit from other structs.

- self-hosted (implemented in itself) since 2011

Rust was created at Mozilla by Graydon Hoare, with contributions from Dave Herman, Brendan Eich, and others. It was formally announced in 2010. Version 1.0 was released in May 2015. A new point release is made every six weeks.

From rust-lang.org, "Every two or three years, we'll be producing a new edition of Rust. Each edition brings together the features that have landed into a clear package, with fully updated documentation and tooling."

The Rust Foundation was announced in February 2021. It is "an independent non-profit organization to steward the Rust programming language and ecosystem." The initial member companies include AWS, Google, Huawei, Microsoft, and Mozilla.

Rust developers are referred to as "Rustaceans" which is derived from the word "crustaceans". Rust mascot is Ferris the crab, a crustacean. The name is fitting because ferrous metals are subject to rust. Images of Ferris can be found at rustacean.net.

Why use Rust

Performance:

The best way to get software performance is to use a "systems" language like C, C++, or Rust. One reason these languages are fast is because they do not provide automatic garbage collection, which is slow and can run at unpredictable times. Systems languages also allow control over whether data is on the stack (faster, but data must have a fixed size) or on the heap (slower, but data can vary in size).

Safety:

Software written in systems languages typically must take great care to avoid memory and threading issues. Memory issues include dangling pointers (accessing memory after it has been freed), memory leaks (failing to free memory that is no longer needed), and double frees (freeing memory more than once). These result in unpredictable behavior. Threading issues include race conditions where the order in which code runs is unpredictable, leading to somewhat random results. Rust addresses both of these issues, resulting in code that is less likely to contain bugs.

Immutable by default:

A large source of software errors involves incorrect assumptions about where data is modified. Making variables immutable by default and requiring explicit indication of functions that are allowed to modify data significantly reduces these errors.

Ownership model:

Manual garbage collection, where developers are responsibly for allocating and freeing memory, is error prone. Automatic garbage collection is relatively slow and requires runtime support which consumes memory. Rust does not use either form of garbage collection. It instead enforces an ownership model where code is explicit about the single scope that currently owns each piece of data. Unless ownership is transferred to another scope, when that scope ends the data is safely freed because no other scope can possibly be using the data. The "borrow checker" in the Rust compiler enforces this at compile time.

Zero-Cost Abstractions:

Rust strives for zero-cost abstractions characterized by this quote from Bjarne Stroustrup, the creator of C++: "What you don't use, you don't pay for. And further: What you do use, you couldn't hand code any better." Rust supports many abstractions that make code more clear, but are optimized by the compiler so there is little to no impact on performance or the amount of machine code that is generated. One example is the use of generic functions that are compiled to separate versions for each concrete type with which they are used. This eliminates the need for runtime dynamic dispatch and is referred to as "monomorphism".

Control over number sizes:

One way to achieve performance in computationally intensive tasks is to store collections of numbers in contiguous memory for fast access and specify the number of bytes used by each number. Rust supports a wide variety of number types for integer and floating point values of specific sizes.

WebAssembly:

WebAssembly (abbreviated WASM) is a binary instruction format for a stack-based virtual machine that is supported by modern web browsers (currently Chrome, Edge, Firefox, and Safari). WASM code typically executes faster than equivalent code written in JavaScript. Code from many programming languages can be compiled to WASM. In 2021 full support is only available for C, C++, and Rust. Experimental support is available for C#, Go, Java, Kotlin, Python, Swift, TypeScript, and a few other less commonly used languages.

In order to run WASM code in a web browser, the runtime of the source language must be included. Rust is a great choice for targeting WASM because it has a very small runtime compared to options like Python, so it downloads faster.

Complexity Tradeoff Systems languages tend to be more complex that non-systems languages, requiring more time to learn and more time to write software in them. Rust is no exception. But many developers choose to use Rust in spite of this in order to gain the benefits described above. On the positive side, the Rust compiler catches many errors that would only be discovered at runtime with other systems languages. The Rust compiler also provides very detailed error messages that often include suggestions on how to correct the errors.

Why use another programming language

Not Performance Critical:

If programming languages that provided automatic memory management (such as JavaScript/TypeScript, Python, and Go) are fast enough for the target application, and garbage collection pauses are not an issue, the effort required to learn and use Rust may be hard to justify. For many developers, this is the case for everything they write.

Learning Curve:

The learning curve for Rust is quite high. It may be too much effort to bring an entire team up to speed on using it. Just learning how to use strings in Rust is a challenge. Developers must constantly think about which scope "owns" each piece of data and decide whether values or references should be passed to functions. They must think about whether values have sizes that are known at compile-time. Generic types are used heavily (for example, in error handling), and often generic types are nested.

Incompatible Libraries:

If an application needs to use non-Rust libraries that are difficult to use from Rust, it may be better to use a more compatible programming language.

Processor Target:

If the target platform uses a processor type that is not a target of LLVM, Rust cannot currently produce code that will run on it.

Compiler Speed:

The Rust compiler is notoriously slow, but it has been getting faster. Slow compile times can negatively affect developer flow because they make it difficult to quickly try alternate coding approaches. The introduction of multiple companies participating in the newly formed "Rust Foundation" will likely lead to improvements in this area. Testing new and modified functions with unit tests rather than in the context of an application that uses them can reduce the time to test changes.

Installing

It is recommended to install Rust using the rustup tool. This enables having multiple versions of Rust installed and switching between them.

To install rustup in macOS:

- Install "Command Line Tools for Xcode" from developer.apple.com (requires a free Apple ID)

- Install homebrew.

- Enter

brew install rustup

Enter the following command to install rustup in Linux (or macOS):

curl --proto '=https' --tlsv1.2 -sSf https://sh.rustup.rs | shTo install rustup in Windows, use Chocolately or Scoop.

For more details, see Other Rust Installation Methods.

After installing rustup, enter rustup-init. This installs many toolchain items including cargo (build/run tool), clippy (linter), rust-docs (documentation), rust-std (standard library), rustc (compiler), and rustfmt (code formatter). It also configures the use of Rust in the bash and zsh shells. When using the fish shell, add the following in .config/fish/config.fish:

set -x PATH $PATH $HOME/.cargo/binVerify the installation by entering rustc --version which should output the version of the rustc command that is installed.

Once installed, to update the versions of all the Rust tools enter rustup update.

Learning Resources

Resources for learning Rust include:

Take your first steps with Rust from Microsoft

rustup doccommandThis displays local documentation that is installed along with Rust in the default web browser. It can be read even when offline. This includes links to the following:

- API documentation

Tip: When reading API documentation, if a "Go to latest version" link appears in the page header, indicating you are not looking at the latest version of the documentation, click it to see the latest. - "The Rust Programming Language" book

- "Rust by Example" book

- "The Rust Reference" book which is more detailed than "The Rust Programming Language" book

- "The Cargo Book" book

- and much more

- API documentation

The Rust Programming Language book

This is a free, open source book. A print copy can be purchased from No Starch Press.

This is "the primary reference for the Rust programming language".

This is a "collection of simple examples that demonstrate good practices to accomplish common programming tasks".

This is a free, online set of examples in many categories.

Rust Standard Library API documentation

Programming Rust book (O'Reilly)

Rust in Motion video course (Manning)

Doug Milford Rust Tutorial series YouTube videos

Jon Gjengset Crust of Rust YouTube videos

Ryan Levick Introduction to Rust YouTube videos

This "contains small exercises to get you used to reading and writing Rust code".

This provides "code practice and mentorship for everyone". The exercism site includes exercises across 52 languages.

This includes "a bunch of links to blog posts, articles, videos, etc for learning Rust."

Terminology

TODO: Add more terminology in this section? ownership, borrow checker, ...

- Cargo

- a command-line utility for building and running Rust programs

- Clippy

- a code linter with over 400 checks for correctness, style, complexity, an performance

- crate

- a Rust program (binary) or library

- contains a tree of modules

- crates.io

- repository of Rust crates, similar to npm for JavaScript

- enum

- a named type whose values come from a list of named variants

- in Rust, these variants can have associated data

- a key feature of Rust error handling

- future

- represents the result of an operation that will complete in the future, similar to a JavaScript

Promise

- represents the result of an operation that will complete in the future, similar to a JavaScript

- generic

- a parameterized type that enables storing and using multiple types of data

- lifetime

- the time period during which a variable can be accesses, starting when it is created and ending when it is freed (a.k.a dropped)

- often associated with the scope of a particular code block

- macro

- a function-like construct whose name ends in

!and generates code at compile-time

- a function-like construct whose name ends in

- module

- a set of related values such as constants and functions

- package

cargofeature for building, testing, and sharing crates- a set of crates described by a

Cargo.tomlfile - contains any number of binaries and 0 or 1 library

- panic

- represents an unrecoverable error that causes a program to terminate, print a stack trace, and print an error message

- struct

- a named collection of fields similar to a class in other languages

- can have associated functions and methods

- trait

- a named collection of constants, function signatures, and optional default implementations

- similar to interfaces in other languages

- TOML

- a configuration file format used by Cargo

- stands for Tom's Obvious, Minimal Language

Rust Playground

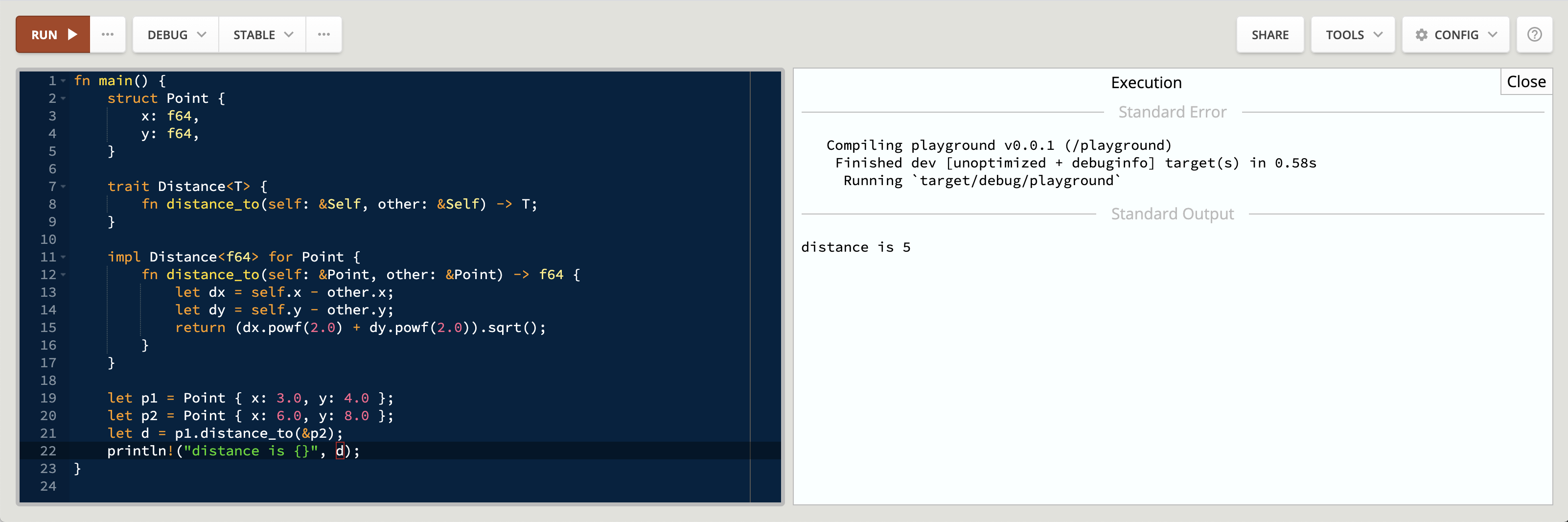

To try Rust code online, browse the Rust Playground. This includes access to the top 100 most downloaded crates (libraries) from crates.io and crates from the Rust Cookbook.

A good use for the Rust Playground is to copy code examples from this blog post into it and run them. Then make changes to the code to try variations and expand your knowledge.

The example code shown in the screenshot below will be more clear after structs and traits are explained.

All of the code must be entered in a single editor pane, simulating being in the single source file main.rs.

Press the ellipsis after the "RUN" button to open a popup with the following options:

- "Run" to build and run the code (

cargo run) - "Build" to only build the code (

cargo build) - "Test" to build the code and run the tests (

cargo test)

Test functions must be preceded by#[test]and nomainfunction can be present. - "ASM" to build the code and show the generated assembly code

- "LLVM IR" to build the code and show the generated LLVM intermediate representation (IR)

- "MIR" to build the code and show the generated mid-level intermediate representation (MIR)

- "WASM" to build a WebAssembly module for use in web browsers

The "RUN" button will change to the last selected option so it can be re-executed by simply pressing the button.

Press the "DEBUG" button to open a popup for choosing between "Debug" and "Release" build modes. A debug build completes in less time because it performs less optimization.

Press the "STABLE" button to open a popup for choosing a Rust version which can be "Stable channel" (default), "Beta channel", or "Nightly channel". The button text changes to indicate the selected version.

Press the ellipsis after the version button to open a popup with the following options:

- "Edition" sets the Rust edition to 2018 (default) or 2015

- "Backtrace" to disable (default) or enable display of backtraces when a panic occurs which slows performance a bit.

Press the "SHARE" button to open a panel on the right side containing the following links:

- "Permalink to the playground" changes the URL to one which will recall the current code, set to run with the currently selected version of Rust.

- "Direct link to the gist" navigates to the URL of the GitHub Gist where the code is stored. The code can be viewed, but not executed from here.

- "Embed code in link" changes the URL to one which includes a base 64 encoded copy of the code as a query parameter. This is only appropriate for small code samples due to URL length limits.

- "Open a new thread in the Rust user forum" does what the link implies, making it easy to ask questions about a code sample. Use this frequently while learning!

- "Open an issue on the Rust GitHub repository" makes it easy to report a bug in Rust.

Press the "TOOLS" button to open a popup with the following options:

- "Rustfmt" formats the code using the

rustfmttool. - "Clippy" runs the Clippy code linter with over 400 checks for correctness, style, complexity, an performance.

- "Miri" runs the program using the Miri interpreter which is an experimental interpreter for Rust's mid-level intermediate representation (MIR). It can detect some bugs not detected by pressing the "RUN" button.

- "Expand macros" displays the code in the right panel with all the macro calls expanded in order to see what they actually do. For example, try this with a

mainfunction that just calls theprintln!macro to print "Hello".

Press the "CONFIG" button to open a popup with the following options:

- "Style" enables switching between "SIMPLE" (no line numbers) and "ADVANCED" (line numbers).

- "Keybinding" enables choosing between keybindings supported by the Ace (Cloud9) editor which is used by this tool. Options include ace, emacs, sublime, vim, and vscode.

- "Theme" enables choosing between 30+ themes including cobalt, github, solarized light, solarized dark.

- "Pair Characters" automatically inserts closing

),}, and]characters after the(,{, and[characters are typed. - "Orientation" enables choosing how panes are arranged. Options include Horizontal, Vertical, and Automatic which chooses based on window size.

- Advanced options control generated assembly code.

There doesn't seem to be a way to select a font for the code.

Configuration options are saved in browser Local Storage so they can be applied to future sessions. The most recently entered code is also saved in Local Storage, but previously entered code is not retained.

Compiling and Running

Rust source files have a .rs file extension.

Here are the steps to compile a Rust source file that defines a main function, create an executable with the same name and no file extension, and run the executable:

- open a terminal (or Windows Command Prompt),

- cd to the directory containing the

.rsfile - enter

rustc name.rs - in macOS or Linux, enter

./name - in Windows, enter

name

For example, the following is a Rust Hello World program:

fn main() {

println!("Hello World!");

}Calls to names that end in !, like println!, are calls to a macro rather than a function.

Typically the rustc command is not used directly. Instead the cargo command, described in the Cargo section, is used to run rustc and the resulting executable.

VS Code

If VS Code is being used to edit Rust code, there are two main extensions to consider: "Rust" and "Rust-analyzer". Both offer similar features which include:

- syntax highlighting

- code completion

- code formatting

- type documentation on hover

- linting with error indicators and the ability to apply suggestions

- code snippets

- rename refactoring

- debugging

- running build tasks

To enable Rust code formatting, add the following in settings.json where FORMATTER is "rust-lang.rust" for the Rust extension and "matklad.rust-analyzer" for the "Rust-analyzer" extension.

"[rust]": {

"editor.defaultFormatter": FORMATTER,

"editor.insertSpaces": true,

"editor.tabSize": 4

},By default Rust-analyzer displays inferred types inline in code, which can be beneficial but is also verbose and distracting. This can be disabled in Settings by searching for "rust analyzer" and unchecking "Rust-analyzer > Inlay Hints: Type Hints". Inferred types can still be displayed by hovering over a variable.

These extensions only work properly if the root folder of a Rust project is opened and it contains a Cargo.toml file. See the Cargo section for details on creating this.

TOML

TOML is a configuration file format that maps to a hash table. The Rust Cargo tool uses this format for Cargo.toml configuration files.

Each key/value pair is described by a line with the syntax key = value. Keys are not surrounded by any delimiters.

Supported value data types include string, integer, float, boolean, datetime, array (an ordered list of values), and table (a collection of key/value pairs). String values are surrounded by double quotes. Datetime values have the format yyyy-mm-ddThh:mm:ss. The time portion can be omitted or be followed by a time zone which is Z for UTC or +hh:mm for a specific offset. Array elements are surrounded by square brackets and separated by commas.

Comments begin with the # character and extend to the end of the line.

Sections and sub-sections are indicated by lines containing a name enclosed in square brackets. Think of these like keys whose values are objects.

Here is the default Cargo.toml file that is created by the command cargo new project-name which we will learn about in the next section:

[package]

name = "delete-me"

version = "0.1.0"

authors = ["R. Mark Volkmann <r.mark.volkmann@gmail.com>"]

edition = "2018"

# See more keys and their definitions at

# https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

[dependencies]Cargo

The cargo command is a CLI tool that is installed with Rust. While using it is not required, it is highly recommended.

For help, enter cargo --help or just cargo.

The following table describes the cargo subcommands:

| Subcommand | Description |

|---|---|

bench | runs benchmarks for the project which are special kinds of tests |

build | builds the project in the target directory |

check | verifies that the project builds successfully, without generating code |

clean | deletes the target directory |

clippy | runs all project source files through the Clippy linter |

doc | generates documentation for the current project |

fmt | formats all project source files using rustfmt |

init | creates a new Rust project in the current directory |

install | installs the project executable, by default in ~/.cargo/bin |

new | creates a new Rust project in a new subdirectory |

publish | publishes the project crate in the crates.io registry |

run or r | builds and runs the project |

search name | searches the crates.io registry for matching crates |

test or t | runs the project tests |

uninstall | removes the project executable, by default from ~/.cargo/bin |

update | updates dependencies in the Cargo.lock file |

The most commonly used cargo subcommands are described in more detail below.

The cargo new command creates a new directory containing a Rust project that is initialized as a new Git repository. It contains a Cargo.toml configuration file that specifies the project name, version, authors, the Rust edition to use, and a list of dependencies. The created directory also contains a src directory containing a single file. When the --lib switch is not included, the file is main.rs which is a simple hello world program. When the --lib switch is included, the file is lib.rs which contains a simple unit test.

In Node.js, project source files can use dependencies listed in their package.json file AND also their dependencies recursively. But Rust project source files can only use dependencies listed in their Cargo.toml file. This has the benefit that a dependency can drop one of its dependencies without breaking apps that use it because a Rust application or library must explicitly list all of its dependencies.

The cargo run command builds and runs the project. It also downloads dependencies listed in the Cargo.toml file, and their dependencies recursively, that have not yet been downloaded. This command can be slow when run for the first time in a new project or if new dependencies have been added since the last time it was run.

To pass command-line arguments to a program, specify them after --.

For example, cargo run -- arg1 arg2

To watch project files for changes and automatically run a cargo command when they do, enter cargo install cargo-watch one time and then enter cargo watch -x subcommand. If the -x option is omitted, the subcommand defaults to check, not run. Typically the desired subcommand is run.

The cargo build command creates a non-optimized executable in the target/debug directory. To create an optimized, production build, enter cargo build --release which creates an executable in the target/release directory.

Naming Conventions

In general, names of types use PascalCase and names of values use snake_case. The compiler outputs warnings when the naming conventions described in the table below are not followed.

| Item | Naming Convention |

|---|---|

| constants | SCREAMING_SNAKE_CASE |

| constructor functions | snake_case |

| crates | snake_case or kebab-case |

| crate features | no convention |

| enums | PascalCase |

| enum variants | PascalCase |

| file names | snake_case or kebab-case |

| functions | snake_case |

| lifetimes | 'lowercase |

| macros | snake_case! |

| methods | snake_case |

| modules | snake_case |

| statics | SCREAMING_SNAKE_CASE |

| structs | PascalCase |

| traits | PascalCase |

| type parameters (generics) | PascalCase, but usually one letter |

| type aliases | PascalCase |

| variables | snake_case |

Syntax Highlights

- Rust prefers short keywords. Examples include

constfor constant,fnfor function,isizefor integer types,implfor implement,letfor variable declarations,modfor module,mutfor mutable,pubfor public,usizefor unsigned integer types, andusefor imports. - Strings are delimited by double quotes.

- Single characters are delimited by single quotes.

- Items (like functions, structs, and struct members) are made public using the

pubkeyword. - A dot (

.) character is used to access struct fields and call instance methods. - A double colon (

::) is used as a namespace separator (borrowed from C++) and to call "associated functions" (like class or static methods in other languages). - Conditions for conditional logic and iteration are not surrounded by any delimiter (no parentheses).

- Statements associated with conditional logic and iteration must be in blocks surrounded by curly braces.

- The preferred indentation is four spaces.

- Named functions are declared with the

fnkeyword. - Function return types follow the parameter list and the characters

->. - Functions that return nothing omit

->and the return type. - Statements must terminated by a semicolon.

- If the last evaluated expression in a function does not end with a semicolon, its value is returned.

- Most statements are also expressions and evaluate to a value, including the

ifandmatchstatements. - There is no null type or value. Instead the

OptionenumNonevariant used.

Comments

Rust supports regular comments and "doc comments".

| Syntax | Usage |

|---|---|

// | extends to end of current line |

/* ... */ | can span multiple lines |

/// | doc comment preceding the item it describes |

//! | doc comment inside the block of the item it describes |

"Doc comments" are included in HTML documentation that is generated by entering cargo doc. This creates the directory target/doc/crate-name and writes HTML for the documentation there.

To generate the documentation and open it in the default browser, enter cargo doc --open. Optionally add the --no-deps flag to avoid building documentation for crate dependencies.

Doc comments optionally include sections with titles that begin with #. Common sections include:

# ExamplesThis section provides code examples in Markdown fences. It is especially useful to demonstrate calls to functions and methods. For library crates (not for binary crates) this code is executed along with other test code by the

cargo testandrustdoc --testcommands.# ErrorsThis section describes any errors that can be returned by the code in a

Resultenum which hasOkandErrvariants.# PanicsThis section describes scenarios that can cause the code to panic.

# SafetyFor functions marked as

unsafe, this section explains why. It also describes what callers must do to use it safely.

Let's walk through a simple example of code that includes a doc comment with an "Examples" section. The vec! macro, iter method, and sum method are described in more detail later. For now all you need to know is that the vec! macro creates a list of values, the iter method returns an iterator over the values, and the sum method adds all the values provided by the iterator. In this case all the values have the type f64 which is an 8-byte floating point value.

Create a library project by entering

cargo new math --lib.Edit the file

src/lib.rsand replace its content the following:/// # Examples

///

/// ```

/// let numbers = vec![1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0];

/// assert_eq!(math::average(&numbers), 2.5);

/// ```

pub fn average(numbers: &Vec<f64>) -> f64 {

let sum: f64 = numbers.iter().sum();

sum / numbers.len() as f64 // return value

}Run the doc comment examples as tests by entering

cargo test.

Attributes

Rust attributes are like "decorators" in other programming languages. They annotate an item in order to change its behavior. An attribute can be specified immediately before an item with the syntax #[attr], inside the block of an item with the syntax #![attr], or at the top level of a source file. When used at the top level, #![attr] specifies a crate-wide attribute.

The following table summarizes commonly used built-in attributes.

| Attribute | Description |

|---|---|

allow(warning1, warning2, ...) | suppresses the specified linting rule warnings |

derive(name1, name2, ...) | automatically implements traits or applies "derive macros", often on a struct |

doc | provides an alternate way to specify and format doc comments |

should_panic | indicates that a test function is expected to panic |

test | indicates that a function is a test |

For a list of linting rules that produce warnings, see Warn-by-default lints. Examples include dead_code, unreachable_code, unused_assignment, unused_imports, and unused_variables. These warnings can be disabled using the allow attribute.

The table of provided traits in the "Traits" section indicates those can be automatically implemented using the derive attribute. For more detail, see Derive.

For more built-in attributes, see the list in "The Rust Reference" at Attributes.

Custom attributes can be implemented by defining attribute-like macros.

Formatted Print

The std namespace, pronounced "stood", defines many commonly used values. The std::fmt namespace defines macros that format text.

| Macro Name | Description |

|---|---|

print! | writes to stdout |

println! | same as print!, but adds a newline |

eprint! | writes to stderr |

eprintln! | same as eprint!, but adds a newline |

format! | writes to a String |

All of these macros take a formatting string followed by zero or more expressions whose values are substituted into the formatting string where occurrences of {} appear. For example:

println!("{} is {}.", "Rust", "interesting"); // Rust is interesting.To print a representation of a value for debugging purposes on a single line, use {:?}. To print each field of a struct on separate lines, use {:#?}. Custom structs must implement the Debug trait in order to use these. The easiest way to do this is to add the attribute #[derive(Debug)] before struct definitions.

The following table summarizes what each of the supported format arguments produce.

| Format Argument | Description |

|---|---|

{} | value of next argument |

{:?} | debugging value on single line |

{:#?} | debugging value on multiple lines |

{n} | value of argument at zero-based index n |

{name} | value with a given name |

{:.n} | number with n decimal places |

{:.*} | number with specified number of decimal places |

{:#X} | number as uppercase hexadecimal |

{:#x} | number as lowercase hexadecimal |

{:<n} | value left justified in a width of n |

{:>n} | value right justified in a width of n |

{:^n} | value centered in a width of n |

Here are some examples:

let n = 3;

println!("{} {}", n * 2, n * 3); // 6, 9

println!("{2} {1}", n * 2, n * 3); // 9, 6

println!("{double} {triple}", double = n * 2, triple = n * 3); // 6 9

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Point2D {

x: f64,

y: f64

}

let p = Point2D { x: 1.0, y: 2.0 }; // constructs a struct instance

println!("{:?}", p); // Point2D { x: 1.0, y: 2.0 }

println!("{:#?}", p);

// Point2D {

// x: 1.0,

// y: 2.0,

// }

println!("{1} {0} {2} {1}", "red", "green", "blue"); // green red blue green

println!(

"{red} {green} {blue}",

blue="00F", green="0F0", red="F00"); // F00 0F0 00F

let pi = std::f64::consts::PI;

println!("{:.4}", pi); // 3.1416

println!("{:.*}", 4, pi); // 3.1416

println!("{:#X}", 15); // 0xF

println!("{:#x}", 15); // 0xf

println!("A{:<5}Z", 123); // A123 Z

println!("A{:>5}Z", 123); // A 123Z

println!("A{:^5}Z", 123); // A 123 ZHere is an example of customizing the way a struct is formatted as a string:

use std::fmt;

struct Point2D {

x: f64,

y: f64

}

impl fmt::Display for Point2D {

// Using "self" as the name of the first parameter makes this a method.

// The second parameter "fmt" must be a mutable reference.

// This method renders a value with the type "fmt::Result".

fn fmt(&self, formatter: &mut fmt::Formatter) -> fmt::Result {

write!(formatter, "(x:{}, y:{})", self.x, self.y)

}

}

fn main() {

let pt = Point2D { x: 1.2, y: 3.4 };

println!("{}", pt); // (x:1.2, y:3.4)

}For more formatting options, see std::fmt.

Variables

Rust variables are immutable by default. For variables that hold non-primitive values such as arrays, tuples, and structs, even their elements/fields cannot be mutated.

The mut keyword marks a variable or parameter as mutable. For variables that hold non-primitive values such as arrays, tuples, and structs, the variable can be changed to point to a different value AND their elements/fields can be mutated.

A variable declaration has the syntax let[ mut] name[: type][ = value]; where optional parts are surrounded by square brackets. The colon and type can be omitted if the desired type can be inferred from the value. A value must be assigned before the variable is referenced. For example:

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Point2D {

x: f64,

y: f64

}

fn main() {

let p: Point2D = Point2D { x: 1.0, y: 2.0 }; // can assign in declaration

println!("p = {:?}", p); // Point2D { x: 1.0, y: 2.0 }

let p: Point2D; // shadows previous declaration (described later)

p = Point2D { x: 1.0, y: 2.0 }; // can assign after declaration

println!("p = {:?}", p); // Point2D { x: 1.0, y: 2.0 }

//p = Point2D { x: 1.2, y: 3.4 }; // cannot change value

//p.x = 5.6; // cannot change a field in current value

let mut p = Point2D { x: 1.0, y: 2.0 };

println!("p = {:?}", p); // Point2D { x: 1.0, y: 2.0 }

p = Point2D { x: 1.2, y: 3.4 }; // can change value

println!("p = {:?}", p); // Point2D { x: 1.2, y: 3.4 }

p.x = 5.6; // can change a field in current value

println!("p = {:?}", p); // Point2D { x: 5.6, y: 3.4 }

}There are five ways to declare a variable.

| Syntax | Meaning |

|---|---|

let name: type = value; | immutable variable that must be assigned a value before it is used |

let mut name: type = value; | mutable variable that must be assigned a value before it is used and can be modified |

const name: type = value; | constant that must be assigned a compile-time expression when it is declared, not the result of a function call |

static name: type = value; | immutable variable that lives for the duration of the program |

static mut name: type = value; | mutable variable that lives for the duration of the program; can only access in unsafe blocks and functions |

Variables defined with static are given a fixed location in memory and all references refer to the value at that location. Their lifetime is 'static which is the duration of the program.

Variables defined with const do not have a location in memory. The compiler substitutes their value where all references appear, so the variable doesn't exist at runtime. In that sense they do not have a lifetime.

Declarations of const and static variables must be explicitly typed, rather than inferring a type based on the assigned value. One rationale is that because their scope can extend to the entire crate, it is better to be explicit about the desired type.

Constants can be defined using either const or static. Using static is preferred for values that are larger than a pointer. This is because the value of a const variable is copied everywhere it is used, unlike the value of a static variable that is shared. In order to assign static variables to other variables, their type must implements the Copy trait because the assignment requires copying. All of the scalar types like bool, char, i32, and f64 implement the Copy trait.

Here are examples of using const and static variables:

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Color {

r: u8,

g: u8,

b: u8,

}

const PURPLE_C: Color = Color { r: 255, g: 0, b: 255 };

static PURPLE_S: Color = Color { r: 255, g: 0, b: 255 };

static mut SIZE: u8 = 1;

fn main() {

println!("{:?}", PURPLE_C); // Color { r: 255, g: 0, b: 255 }

println!("{:?}", PURPLE_S); // Color { r: 255, g: 0, b: 255 }

let v = PURPLE_C; // allowed

//let v = PURPLE_S; // error: cannot move out of static item

println!("{:?}", v); // Color { r: 255, g: 0, b: 255 }b

unsafe {

println!("{}", SIZE); // 1

change_it();

use_it(); // 2

}

}

unsafe fn change_it() {

SIZE = 2; // mutates "static mut" variable

}

unsafe fn use_it() {

println!("{}", SIZE); // 2

}To print the type of a variable for debugging purposes, define the following function and pass a reference to it:

fn print_type<T>(_: &T) {

// The syntax ::<T> is referred to as the "turbofish" qualifier.

// It specifies a type in the middle of an expression.

// In this case it is a generic type.:

println!("{}", std::any::type_name::<T>())

}

fn main() {

let v = 19;

print_type(&v); // i32

}Rust allows variables to be re-declared with a different type in the same block. This is referred to as "shadowing". Sometimes this is preferred over coming up with multiple names for the same concept. For example:

let command = "order 3 tacos"; // &str

// The str split_whitespace method returns an Iterator.

// The Iterator nth method returns an Option

// whose value can be obtained in many ways.

// One way is to call unwrap_or, passing it

// a value to return if no value is found.

let quantity = command.split_whitespace().nth(1).unwrap_or(""); // &str

// Parse the string value to create an i32 value.

let quantity = quantity.parse().unwrap_or(0);

if quantity > 2 {

println!("You must be very hungry!")

} else {

println!("Perhaps you don't really like tacos.")

}Ownership Model

Memory management in Rust is handled by following these rules, referred to as the ownership model:

- Each value is referred to by a variable that is its owner.

- Each value has one owner at a time, but the owner can change over its lifetime.

- When the owner variable goes out of the scope, the value is dropped (freed).

The ownership model provides the following benefits:

- Runtime speed is achieved by eliminating the need for a garbage collector (GC).

- Performance is more predictable because there are no GC pauses.

- Memory access is safer since there is no possibility of null pointer accesses or dangling pointer accesses (accessing memory that has already been freed).

- Parallel and concurrent processing is safer because there is no possibility of data races causing unpredictable interactions between threads.

Values are stored either in the stack or the heap. Accessing stack data is faster, but data on the heap can grow and shrink, and it can live beyond the scope that created it.

Values whose sizes are known at compile time are stored on the stack. Values of all other types are stored in the heap. The documentation for types whose size is not known at compile time indicates this with ?Sized. These include:

- slices, not references to them

- string slice types

strandOsStr std::path::Pathfor representing and operating on file system paths- trait objects (

dyn TraitName) - structs and tuples for which the last field/item has one of these types

Values of types whose sizes are not known at compile time can be stored on the heap by using the Box type. This provides a fixed size way to refer to a value that does not have a fixed size. An example is returning an error struct whose specific type is selected at run time based on the kind of error that occurs. Another example is a recursive type such as linked list.

All code blocks are delimited by a pair of curly braces and create a new scope. Variables declared in each new scope add data to the stack that is freed when that scope exits. Many keywords have an associated block, including fn, if, loop, for, and while.

The Drop trait can be implemented for any type to specify code to execute (in the drop method) when data of that type is dropped.

While it is not typically called directly, std::mem::drop is a function that can be called to explicitly free the memory owned by a variable before it goes out of scope.

The following table summarizes the options for assigning a variable to another or passing a variable an argument to a function.

| Goal | Syntax |

|---|---|

| transfer ownership | name |

| copy | name |

| borrow immutably | &name |

| borrow mutably | &mut name |

The difference between the first and second cases is entirely based on whether the type of the data implements the Copy trait.

Having all of these options requires considering the following questions for every variable being passed to a function or assigned to another variable:

- Do I want to transfer ownership? Often the answer is "no".

- Does the receiver need to modify the value? Often the answer is "no".

- Do I want to avoid making a copy for efficiency? Often the answer is "yes".

- If I want to pass a copy, will one be made automatically or do I need to explicitly clone it?

Here are some examples that demonstrate ownership inside a single function. See the Strings section for more detail on the differences between the String and &str types.

fn main() {

let a = 1;

// Because a has a scalar type (fixed size) that implements the Copy trait,

// this makes a copy of a and assigns that to b

// rather than moving ownership from a to b.

// Both a and b can then be used.

let b = a;

println!("{}", a); // 1

println!("{}", b); // 1

// This creates a String instance from a &str value.

let c = String::from("test");

// Because c is on the heap and String does not implement

// the Copy trait, this moves ownership from c to d

// and c can no longer be used.

let d = c;

//println!("c = {}", c); // error: value borrowed here after move

println!("d = {}", d); // test

// The Copy trait requires also implementing the Clone trait.

// We can implement these traits manually, but that is more work.

// The easiest way to implement them is with the derive attribute.

#[derive(Clone, Copy, Debug)]

struct Point2D {

x: f64,

y: f64

}

let e = Point2D { x: 1.0, y: 2.0 };

// Since we implemented the Copy trait on the Point2D type,

// this makes a copy of e and assigns it to f.

// If we hadn't implemented the Copy trait,

// this would move ownership from e to f.

let f = e;

println!("f = {:?}", f); // Point2D { x: 1.0, y: 2.0 }

// This works because we implemented the Copy trait.

// If we hadn't, we would get the error "value borrowed here after move".

println!("e = {:?}", e);

}Ownership of a value can be "borrowed" by any number of variables by getting a reference to a value. For example:

let e = Point2D { x: 1.0, y: 2.0 };

println!("e = {:?}", e); // Point2D { x: 1.0, y: 2.0 }

let f = &e; // an immutable borrow

let g = &e; // another immutable borrow

println!("f={:?}, g={:?}", f, g); // no errors hereAny variable whose type acts like a pointer to another type (for example, &variable and smart pointers like Box, Rc, and Arc that are described later) can be dereferenced to get the value to which it points. This can be done with the * operator. Automatic dereferencing is performed by the dot operator which is used to access a field or method of a type. Automatic dereferencing also occurs when a reference type is passed to a function or macro. This is why we were able to print f above without specifying *f which also works. Automatic dereferencing makes code less "noisy" than it would otherwise be.

Borrowing does not transfer (also referred to as "move") ownership. A borrowed variable can go out of scope without freeing the memory associated with the original variable.

When a value is mutable and ownership is borrowed, the compiler will report an error if the value is mutated after the borrow is created and before the last use of the borrow. This is because references expect the data they reference to remain the same for the duration of the borrow. For example:

let mut e = Point2D { x: 1.0, y: 2.0 };

let f = &e; // f borrows a reference rather than taking ownership

println!("f = {:?}", f); // works

// The next line mutates e.

// But f which is a mutable borrow is used after this line.

// So we get the error "cannot assign to `e.x` because it is borrowed".

e.x += 3.0;

println!("f = {:?}", f);Often a borrow only needs to read a value (referred to as an "immutable borrow"). Any number of immutable borrows can be created. A mutable borrow allows changing a mutable value through the borrowed variable. But a mutable borrow can only be created when there will be no uses of already created immutable borrows until after the last use of the mutable one. Also, only one mutable borrow of a given variable can be active at a time. The original variable cannot be accessed again until after the last access of the borrowed variable. For example:

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Point2D {

x: f64,

y: f64

}

fn main() {

let mut pt = Point2D { x: 1.0, y: 2.0 };

let ref1 = &pt; // immutable borrow

println!("{:?}", ref1); // Point2D { x: 1.0, y: 2.0 }

// Can create and use any number of additional immutable borrows.

let ref2 = &pt;

println!("{:?}", ref2); // Point2D { x: 1.0, y: 2.0 }

// Can use earlier immutable borrows again.

println!("{:?}", ref1); // Point2D { x: 1.0, y: 2.0 }

// Can create and use a mutable borrow.

let ref3 = &mut pt;

ref3.x = 3.0;

println!("{:?}", ref3); // Point2D { x: 3.0, y: 2.0 }

// Can't use immutable borrows created before a mutable borrow,

// even if the mutable borrow isn't used to mutate the value.

//println!("{:?}", ref1);

// error: cannot borrow `pt` as mutable

// because it is also borrowed as immutable

// Can create and use new immutable borrows because

// we are finished with the mutable borrow at this point.

let ref4 = &pt;

println!("{:?}", ref4); // Point2D { x: 3.0, y: 2.0 }

}An alternative to borrowing is to clone data, but doing this is often unnecessarily inefficient. To clone a value, call its clone method which is available for all types that implement the Clone trait. A large number of built-in types implement this including String, arrays, tuples, Vec, HashMap, and HashSet. To enable cloning a struct, implement the Clone trait by adding the #[derive(Clone)] attribute before it.

When variables whose values are on the stack are passed to functions, the functions are given copies. For example:

fn my_function(x: i32) {

println!("{}", x); // 1

}

fn main() {

let x = 1;

my_function(x); // a copy of x is passed

println!("{}", x); // 1

}When variables (not references) of types that do not implement the Copy trait are passed to functions, copies are not made and ownership is transferred. When the function exits, the data is freed. The calling function can then no longer use variables that were passed. For example:

#[derive(Clone, Copy, Debug)]

struct Point2D {

x: f64,

y: f64

}

fn take_point(p: Point2D) {

println!("p = {:?}", p);

}

fn take_vector(v: Vec<u8>) {

println!("v = {:?}", v);

}

fn main() {

let pt = Point2D { x: 1.0, y: 2.0 };

// A copy is passed because the Point2D type implements the copy trait.

take_point(pt);

// We can still use pt because ownership was not transferred.

println!("pt = {:?}", pt);

let numbers = vec![1, 2, 3];

// Ownership is transferred because

// the Vec type does not implement the Copy trait.

take_vector(numbers); // error: borrow of moved value: `numbers`

// We cannot use numbers here because ownership was transferred.

println!("numbers = {:?}", numbers); // value borrowed here after move

}We can fix the error above by changing the function to return the parameter which returns ownership. For example:

fn take_vector(v: Vec<u8>) -> Vec<u8> {

println!("v = {:?}", v);

v

}

fn main() {

let numbers = vec![1, 2, 3];

let new_numbers = take_vector(numbers);

println!("new_numbers = {:?}", new_numbers);

}When references to variables are passed to functions, ownership is borrowed rather than being transferred. When the function exits, the value is not freed and the calling function can continue using it. For example:

// We could pass the i32 argument by reference,

// but there is no benefit in doing that.

fn my_function(i: i32, s: &String) {

println!("{}", i); // 1

println!("{}", s); // "test"

}

fn main() {

let i = 1;

let s = String::from("test");

my_function(i, &s);

println!("{}", i); // 1

println!("{}", s); // "test"

}To allow a function to modify data passed to it by reference, pass and receive mutable references. For example:

fn my_function(i: &mut i32, s: &mut String) {

println!("{}", i); // 1

*i += 1; // dereferences and increments

println!("{}", s); // "test"

s.push_str(" more");

}

fn main() {

let mut i = 1; // on stack

let mut s = String::from("test"); // on heap

// Even though i and s are mutable, the arguments to

// my_function below only need to be marked as mutable

// if that function requires them to be mutable.

my_function(&mut i, &mut s);

println!("{}", i); // 2

println!("{}", s); // "test more"

}A function can create a value and return it. This transfers ownership to the caller rather than freeing the data when the function exits. For example:

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Point2D {

x: f64,

y: f64

}

fn get_origin() -> Point2D {

Point2D { x: 0.0, y: 0.0 }

}

fn get_string() -> String {

String::from("test")

}

fn main() {

let p = get_origin();

println!("{:?}", p); // Point2D { x: 0.0, y: 0.0 }

let s = get_string();

println!("{}", s); // test

}Early we said that memory for values allocated in a scope is freed when the scope exits. However, there is an exception to this when ownership is transferred outside a block. For example:

fn main() {

let a; // set once inside the block that follows

{

// Allocate inside block.

let b = String::from("test");

// Move ownership to "a" which lives outside this block.

a = b;

// If the previous line is changed to

// a = &b;

// we get the error "`b` does not live long enough"

// because a will no longer get ownership

// and b will be freed at the end of the block.

// Memory for b is not freed when this block exits

// because b no longer owns it.

}

// "a" can be used here because its lifetime has yet not ended.

println!("{}", a);

}Closures are functions that capture values in their environment so they can be accessed later when the function is executed. Functions defined with the fn keyword are not closures. Closures are defined as anonymous functions with a parameter list written between vertical bars which must be present even if there are no parameters. While function parameter and return types must be specified, these can be inferred for closures.

Here is an ownership example that is similar to the previous example, but uses a closure:

fn main() {

// This variable must be initialized in order to access it in the closure.

// Because it is then modified in the closure, it must be mutable.

let mut a = String::new(); // an empty string

// This variable must be `mut` because it captures and mutates

// the mutable variable "a" in its environment.

let mut inner = | | { // no parameters

let b = String::from("test");

a = b; // Moves ownership from b to a.

};

inner();

println!("{}", a); // test

}Here is an example that concisely summarizes the ownership options when passing a value to a function:

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Point2D {

x: f64,

y: f64

}

fn take(pt: Point2D) {

println!("in take, {:?}", pt);

}

fn take_and_return(pt: Point2D) -> Point2D {

println!("in take_and_return, {:?}", pt);

pt // returns ownership to caller

}

fn borrow_immutably(pt: &Point2D) {

//pt.x = 3.0; // can't mutate

println!("in borrow_immutably, {:?}", pt);

}

fn borrow_mutably(pt: &mut Point2D) {

pt.x = 3.0; // can mutate

println!("in borrow_mutably, {:?}", pt);

}

fn main() {

let pt = Point2D { x: 1.0, y: 2.0 };

take(pt); // in take, Point2D { x: 1.0, y: 2.0 }

// Can't use pt after ownership was transferred and not returned.

//println!("after take, pt = {:?}", pt);

let mut pt = Point2D { x: 1.0, y: 2.0 };

pt = take_and_return(pt); // in take_and_return, Point2D { x: 1.0, y: 2.0 }

// Can use after this because ownership is returned.

println!("{:?}", pt); // Point2D { x: 1.0, y: 2.0 }

let pt = Point2D { x: 1.0, y: 2.0 };

borrow_immutably(&pt); // in borrow_immutably, Point2D { x: 1.0, y: 2.0 }

println!("{:?}", pt); // Point2D { x: 1.0, y: 2.0 }

let mut pt = Point2D { x: 1.0, y: 2.0 };

borrow_mutably(&mut pt); // in borrow_mutably, Point2D { x: 3.0, y: 2.0 }

println!("{:?}", pt); // Point2D { x: 3.0, y: 2.0 }

}Here are some guidelines related to ownership of heap data. While there are situations in which these do not apply, often to improve performance, following these will typically reduce ownership issues in your code.

- Compound types should own their heap data rather than hold references to heap data owned elsewhere. For example, struct fields that are strings should use the

Stringtype instead of&str. - Pass references to heap data to functions rather than transferring ownership. For example, a parameter that accepts string data should have the type

&strinstead ofString. An exception is when the function wants to take ownership in order to add items to a compound type that it owns. - In functions that create and return heap data, transfer ownership to the caller. For example, return

Stringrather than&str.

Lifetimes

Lifetimes ensure that memory does not get freed before a reference to it can use it.

Lifetime annotations only apply to references. All reference parameters and reference return types have a lifetime, but in most cases the Rust compiler automatically determines them. It does so using these three simple "lifetime elision" rules:

- Each parameter with a reference type and no specified lifetime parameter is assigned a unique lifetime parameter.

- If all the reference parameters now have the same lifetime and the return type is a reference, it is assigned the same lifetime as the reference parameters. This occurs when there is only one parameter with a reference type or when there is more that one, but they all have the same specified lifetime annotation.

- If the function is a method (indicated by the first parameter having the name

self), theselfparameter is a reference (&selfor&mut self), and the return type is a reference, theselfreference and the return type reference are given the same lifetime parameter. The reason for this is that it is common for such a method to return a reference to part ofself.

If after applying these rules to a function whose return type is a reference the lifetime of the return type is still unknown, the compiler outputs a "missing lifetime specifier". This means that lifetimes must be explicitly specified. Typically explicit lifetime parameters are only needed when there are multiple reference parameters and the return type is a reference. When this is the case, often the same explicit lifetime parameter is added to all of the reference parameters AND the return reference type.

Lifetime annotations used in function signatures are declared by listing them in angle brackets just like generic types. They are distinguish from generic types by beginning with a single quote. Lifetime annotations appear in reference types after the & and before type names. Their names are typically a single letter such as "a". Lifetime annotations only serve to indicate which items in a function signature have the same lifetime (or at least as long as another), not an actual duration.

The following example illustrates a case where lifetime annotations are required:

// The function signature below results in a

// "missing lifetime specifier" error.

// Additionally, the compiler says "explicit lifetime required"

// for s1, s2, and the return type.

// When more than one reference is passed to a function AND

// one of them can be returned, Rust requires lifetime specifiers.

//fn get_greater(s1: &str, s2: &str) -> &str {

// The next function signature includes lifetime specifiers.

fn get_greater<'a>(s1: &'a str, s2: &'a str) -> &'a str {

if s1 > s2 {

s1

} else {

s2

}

}

fn get_surprise(s: &str) -> &str {

return get_greater(s, "no soup for you");

}

fn main() {

println!("{}", get_surprise("soup")); // soup

println!("{}", get_surprise("bread")); // no soup for you

}The name static is a reserved lifetime name. It is the lifetime of const and static values which live for the duration of the program.

To use more than one lifetime specifier in a function signature, list them after the function name inside angle brackets separated by commas. For example, fn my_function<'a, 'b>(...).

To specify that lifetime b is at least as long as lifetime a, use fn my_function<'a, 'b: 'a>(...).

Enums

Enums specify a list of allowed values referred to as "variants". For example:

#[allow(dead_code)] // suppresses warning about not using all the variants

#[derive(Debug)]

enum PrimaryColor { Red, Green, Blue }

fn process_color(color: PrimaryColor) {

println!("{:?}", color); // Green

}

fn main() {

let color: PrimaryColor = PrimaryColor::Green;

process_color(color);

}Match expressions are similar to switch statements in other languages, but they evaluate to a value. Instead of case statements inside a switch they have "match arms". There must be a match arm for every possible value of the expression being matched, i.e. they must be exhaustive. For example:

#[allow(dead_code)]

#[derive(Debug)]

enum PrimaryColor { Red, Green, Blue }

fn main() {

use PrimaryColor::*; // brings all values into current scope

let color = Red;

// If a match arm for any PrimaryColor variant was missing

// we would get a "non-exhaustive patterns" error.

let item = match color {

Red => "stop sign",

Green => "grass",

Blue => "sky",

};

println!("{}", item); // stop sign

let item = match color {

Blue => "sky",

_ => "unknown" // wildcard handling all other values

};

println!("{}", item); // unknown

}The Error Handling section describes the Option and Result generic enums that are provided by the standard library. These contain variants that hold data, which is something that enums in most other programming languages cannot do. The Option<T> enum defines the variants Some(T) and None. The Result<T, E> enum defines the variants Ok(T) and Err<E>.

Enum variants can hold many kinds of values. For example:

use std::fmt::Debug;

#[derive(Debug)]

enum Demo {

Empty,

Single(String),

TupleLike(String, i32, bool), // holds positional items

StructLike{x: f64, y: f64}, // holds named items

}

fn main() {

use Demo::*;

let d1 = Empty;

let d2 = Single(String::from("Hello"));

let d3 = TupleLike(String::from("red"), 19, true);

let d4 = StructLike{x: 1.2, y: 3.4};

println!("{:?}, {:?}, {:?}, {:?}", d1, d2, d3, d4);

// prints Empty, Single("Hello"),

// TupleLike("red", 19, true),

// StructLike { x: 1.2, y: 3.4 }

}Error Handling

Unlike many other programming languages, Rust does not support throwing and catching exceptions. Instead, functions that can fail typically return the enum type Option or Result.

The Option enum has two variants, Some which wraps a value and None which doesn't. For example, a function that takes a vector and returns the first element that matches some criteria could return Some wrapping the element, or None if no match is found. This is similar to the Maybe monad in Haskell.

The Result enum also has two variants, Ok which wraps a value and Err which wraps an error description. For example, a function that reads all the text in a file could return Ok wrapping the text, or Err wrapping a description of why reading the file failed. This is similar to the Either monad in Haskell.

There are many ways to handle variants from these enum types.

Use a

matchstatement.For example:

#[derive(Debug)]

pub enum MathError {

DivisionByZero // used by divide2 function below

}

// Demonstrates returning a Option enum.

fn divide1(numerator: f64, denominator: f64) -> Option<f64> {

if denominator == 0.0 {

None // means there is no result, but doesn't explain why

} else {

Some(numerator / denominator)

}

}

// Demonstrates returning a Result enum.

// Commented lines below show an alternative way

// to describe the error using a string.

//const DIV_BY_ZERO: &str = "divide by zero";

fn divide2(numerator: f64, denominator: f64)

-> Result<f64, MathError> {

//fn divide2(numerator: f64, denominator: f64)

//-> Result<f64, &'static str> {

if denominator == 0.0 {

Err(MathError::DivisionByZero)

//Err(DIV_BY_ZERO)

} else {

Ok(numerator / denominator)

}

}

fn main() {

let n = 5.0;

let d = 2.0;

match divide1(n, d) { // returns an Option enum

Some(result) => println!("{:.2}", result), // 2.50

None => println!("divide by zero"),

}

match divide2(n, d) { // returns a Result enum

Ok(result) => println!("{:.2}", result), // 2.50

Err(e) => println!("{:?}", e),

//Err(msg) => println!("{}", msg),

}

}Use

if letstatement.We can replace the

matchstatements in the previous example with the following:if let Some(result) = divide1(n, d) {

println!("{:.2}", result);

} else {

println!("fail")

}

if let Ok(result) = divide2(n, d) {

println!("{:.2}", result);

} else { // With this approach we lose the detail in the Err variant.

println!("fail")

}Use the

unwrap,unwrap_or,unwrap_or_default, orunwrap_or_elsemethod.These extract the value from an

OptionorResultenum.If the value is a

SomeorOk, these succeed.If the value is a

NoneorErr:unwrappanics, exiting the program.

If the value isErr, the message it wraps will be output.unwrap_oruses a specified value.unwrap_or_defaultuses the default value for the type.

For custom types, this is specified by implementing theDefaulttrait.unwrap_or_elseexecutes a closure passed to it to compute the value to use.

For example, we can replace the

matchandif letstatements above with the following:let result = divide1(n, d).unwrap();

println!("{:.2}", result);

// When d is zero this uses infinity for the value.

let result = divide2(n, d).unwrap_or(std::f64::INFINITY);

println!("{:.2}", result);Use the

expectmethod.This is nearly the same as the

unwrapmethod. The only difference is that a custom error message can be supplied. We can replace the lines above with the following:let result = divide1(n, d).expect("division failed");

println!("{:.2}", result);

let result = divide2(n, d).expect("division failed");

println!("{:.2}", result);Use the

?operator which is shorthand for thetry!macro.This allows the caller to handle errors, similar to re-throwing an exception in other programming languages. It can be applied to functions that return a

ResultorOptionenum.If the value is a

SomeorOkvariant then it is unwrapped and returned. If the value is aNoneorErrvariant then it is passed through thefromfunction (defined in the standard libraryFromtrait) in order to convert it to the return type of the function, and that is returned to the caller.The function in which this operator is used must declare the proper return type and return a value of that type.

let result = divide1(n, d)?;

println!("{:.2}", result);

let result = divide2(n, d)?;

println!("{:.2}", result);Uses of

?can be chained in the same statement. For example, suppose the functionalphareturns aResultwhose wrapped value is an object with a methodbetathat returns aResultwhose wrapped value is an object with a methodgammathat returns aResult. We can get the value of this call sequences with the following:let value = alpha()?beta()?gamma()?;In functions that call multiple other functions that return

Resultinstances with different types of errors and wish to return them to callers, consider making the return typeResult<SomeOkType, Box<dyn std::error::Error>>.Boxis needed to accommodate error values of different sizes because the size of the error value must be known at compile time. ABoxis a smart pointer with a fixed size that points to another value. Thedynkeyword performs dynamic dispatch to allow a value of any type that implements a given trait,Errorin this case. Even themainfunction can be given this return type.In the case below the errors that can be returned (

std::io::Errorandstd::num::ParseIntError) all implement thestd::error::Errortrait. This example comes from the Rustlings exerciseerrorsn.rs.fn read_and_validate(

b: &mut dyn io::BufRead,

) -> Result<PositiveNonzeroInteger, Box<dyn std::error::Error>> {

let mut line = String::new();

// The read_line method can return Err(std::io::Error).

b.read_line(&mut line)?;

// The parse method can return Err(std::num::ParseIntError).

let num: i64 = line.trim().parse()?;

let answer = PositiveNonzeroInteger::new(num)?;

Ok(answer)

}

The following example demonstrates several approaches to error handling for functions that can return multiple error types. To experiment with this code, download it from the GitHub repo named rust-error-handling.

use serde::{Deserialize, Serialize};

use std::error::Error;

use std::fmt;

use std::fs::read_to_string;

// This is a custom error type.

// It enables callers that receive this kind of error

// to handle different error causes differently.

// These must implement the Error trait (done below) which requires

// implementing the Debug (done here) and Display (done below) traits.

#[derive(Debug)]

pub enum GetDogsError {

BadFile(std::io::Error),

BadJson(serde_json::error::Error),

}

// Make the variants of this enum directly available.

use GetDogsError::*;

// All of the Error trait methods have default implementations, so

// no body is required here, but we will implement the source method.

impl Error for GetDogsError {

// Returns the wrapped error, if any.

fn source(&self) -> Option<&(dyn Error + 'static)> {

match *self {

// The wrapped error type is implicitly cast to the trait object

// type &Error because it implements the Error trait.

BadFile(ref e) => Some(e),

BadJson(ref e) => Some(e),

}

}

}

impl std::fmt::Display for GetDogsError {

fn fmt(&self, f: &mut fmt::Formatter) -> fmt::Result {

match *self {

BadFile(ref e) => write!(f, "bad file: {}", e),

BadJson(ref e) => write!(f, "bad JSON: {}", e),

}

}

}

// The "From" trait converts values of one type to another.

// Having the following implementations enables

// using the ? operator in the get_dogs3 function below.

impl From<std::io::Error> for GetDogsError {

fn from(other: std::io::Error) -> Self {

BadFile(other)

}

}

impl From<serde_json::error::Error> for GetDogsError {

fn from(other: serde_json::error::Error) -> Self {

BadJson(other)

}

}

// This struct can be deserialized from JSON and serialized to JSON.

#[derive(Deserialize, Serialize, Debug)]

struct Dog {

name: String,

breed: String,

}

// Let's look at three versions of a function that

// reads a JSON file describing dogs and parses it

// to create a vector of Dog instances.

// With this version callers cannot easily distinguish between

// the two types of errors that can occur,

// std::io:Error from failing to read the file and

// serde_json::error::Error from failing to parse the JSON.

// This approach is fine when callers only need to

// know if an error occurred and print an error message.

fn get_dogs1(file_path: &str) -> Result<Vec<Dog>, Box<dyn Error>> {

let json = read_to_string(file_path)?;

let dogs: Vec<Dog> = serde_json::from_str(&json)?;

Ok(dogs)

}

// If we have many functions with this same return type,

// Result<some-type, GetDogsError> {

// we can reduce the repetition by defining a type alias.

pub type MyResult<T> = std::result::Result<T, GetDogsError>;

// With this version callers can distinguish between the

// two types of errors by matching on the GetDogsError variants.

fn get_dogs2(file_path: &str) -> MyResult<Vec<Dog>> {

match read_to_string(file_path) {

Ok(json) => match serde_json::from_str(&json) {

Ok(dogs) => Ok(dogs),

Err(e) => Err(BadJson(e)),

},

Err(e) => Err(BadFile(e)),

}

}

// This version takes advantage of the fact that

// GetDogsError implements the From trait for

// each of the kinds of errors that can occur.

// This enables using the ? operator because errors of those

// types will automatically be converted to the GetDogsError type.

fn get_dogs3(file_path: &str) -> MyResult<Vec<Dog>> {

let json = read_to_string(file_path)?;

let dogs: Vec<Dog> = serde_json::from_str(&json)?;

Ok(dogs)

}

// If the main function has this return type, it can use the ? operator.

//fn main() -> Result<(), Box<dyn Error>> {

fn main() {

let file_path = "./dogs.json";

/*

// With the first approach we can easily detect

// that an error has occurred.

if let Ok(dogs) = get_dogs1(file_path) {

dbg!(dogs);

} else {

eprintln!("failed to get dogs, but don't know why");

}

*/

/*

// But handling different kinds of errors differently is messy.

match get_dogs1(file_path) {

Ok(dogs) => println!("{:?}", dogs),

Err(e) => {

if let Some(e) = e.downcast_ref::<std::io::Error>() {

eprintln!("bad file: {:?}", e);

} else if let Some(e) =

e.downcast_ref::<serde_json::error::Error>() {

eprintln!("bad json {:?}", e);

} else {

eprintln!("some other kind of error");

}

}

}

*/

// With the second and third approaches it is much easier

// to handle different kinds of errors differently.

//match get_dogs2(file_path) {

match get_dogs3(file_path) {

Ok(dogs) => println!("{:?}", dogs),

Err(BadFile(e)) => eprintln!("bad file: {}", e),

Err(BadJson(e)) => eprintln!("bad json: {}", e),

}

}The quick-error crate makes implementing custom error types easier. Here are the changes required to use this approach which also requires adding quick-error as a dependency in Cargo.toml. Note that we no longer need to manually implement the Error, Display, and From traits for our custom error enum. To experiment with this code, see the quick_error branch of the rust-error-handling GitHub repo.

#[macro_use]

extern crate quick_error;

use serde::{Deserialize, Serialize};

use std::fs::read_to_string;

quick_error! {

#[derive(Debug)]

pub enum GetDogsError {

BadFile(e: std::io::Error) {

display("bad file {}", e)

from()

}

BadJson(e: serde_json::error::Error) {

display("bad json {}", e)

from()

}

}

}Generics

Rust makes heavy use of generic types. They enable implementing functions, structs, and traits that operate on various types of data instead of only specific types.

Generic types are declared inside angle brackets. They can specify one or more traits that must be implemented by concrete types in order to use them in place of the type parameters. The sections on functions, structs, and traits contain many examples of using generic types.

Built-in Types

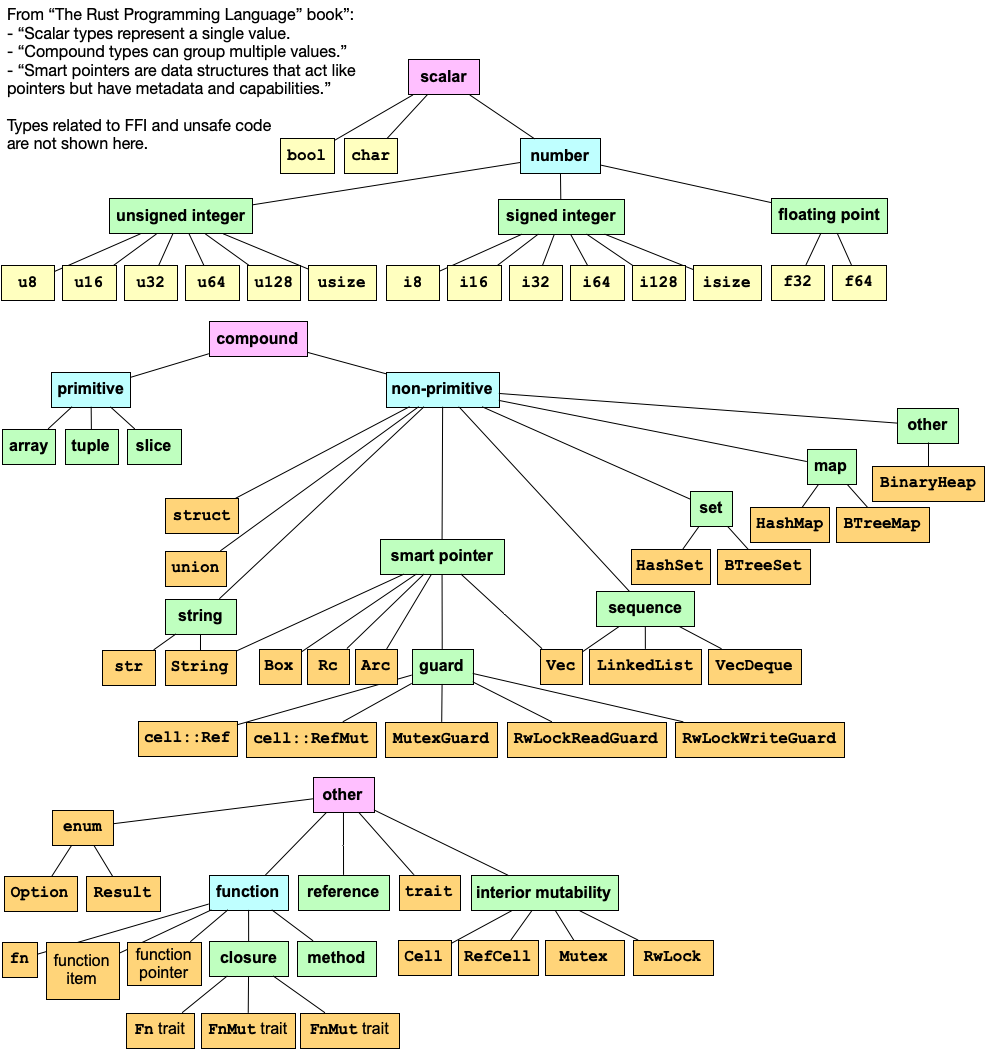

Rust provides many built-types. The following diagram summarizes them.

Built-in Scalar Types

Rust defines many scalar (primitive) types which can be categorized as boolean, character, integer (6 kinds), or floating point (2 kinds).

The boolean type name is bool. Its only values are true and false.

The character type name is char. Literal values are surrounded by single quotes. Its values are Unicode values that each occupy four bytes, regardless of whether four bytes are actually needed to represent them. This gives the values a known size at compile time.

The signed integer type names are i{n} where {n} is the number of bits which can be 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, or size. The isize type matches either i32 or i64 depending on the current processor architecture. The default type for literal integers is i32 regardless of the processor.

The unsigned integer types are the same, but start with u instead of i. The usize type is typically used to index into collections such as arrays and vectors.

Literal number values can end with these type names to make their type explicit. For example, the following variable declarations are equivalent:

let number: i8 = 19;

let number = 19i8;Literal integer values can use the underscore character to separate thousands, millions, and so on. For example, the population of the U.S. in 2020 was approximately 330_676_544.

Hex literal values begin with 0x, octal literal values begin with 0o, and binary literal values begin with 0b.

The floating point type names are f{n} where {n} is 32 or 64. The default type for literal floats is f64 regardless of the current processor. Literal floating point values must include a decimal point to avoid being treated as integer values, but it is acceptable to have no digits after the decimal point. This means that 123. is treated the same as 123.0.

The "unit type" represents not having a value, like void in other languages. It can be thought of as an enum with a single variant which is written as (). It is the return value of functions that do not return a value. It is also what the Result enum Ok variant wraps when there is nothing to return. The unit type value can follow the => in a match arm to take no action.

Rust allows adding methods to any type, even built-in, scalar types. The following example shows added a method to the i32 type:

trait Days<T> {

fn days_from_now(self) -> String;

}

impl Days<i32> for i32 {

fn days_from_now(self: i32) -> String {

let s = match self {

-1 => "yesterday",

0 => "today",

1 => "tomorrow",

_ => if self > 0 { "future" } else { "past" }

};

s.to_string()

}

}

fn main() {

let days: i32 = -1;

println!("{}", days.days_from_now()); // yesterday

println!("{}", 0.days_from_now()); // today

println!("{}", 1.days_from_now()); // tomorrow

println!("{}", 2.days_from_now()); // future

println!("{}", (-2).days_from_now()); // past

}Here is another way to implement this that works on values of any type that implements the traits Eq, Ord, and From<i8> which all the number types do:

use std::cmp::{ Eq, Ord };

trait Days {

fn days_from_now(self) -> &'static str;

}

impl<T: Eq + Ord + From<i8>> Days for T {